Over six years after the Sustainable Development Goals were adopted, business largely continues to suffer from the illusion of choice and to believe that sustainability is an option. Inspired by external experts who research the best narrative to convince business, Your Public Value republishes here a blog that was jointly written by Dominic Tantram from Terrafiniti and Benjamin Jeffery, Sustainability Manager at Refresco Beverages UK, who expresses here his personal views.

Choice is an illusion. So who chooses sustainability?

Choice is a leading aspect of modern life and is a powerful tool in the marketplace. But how much is real and how much of this choice is an illusion? And where does responsibility lie to choose sustainability?

Should it lie with consumers encouraging businesses to converge with their values? Or are the issues so important for long-term wellbeing and quality of life that the appearance of choice is an illusion and businesses must place sustainability in the heart of their business models?

Consumerism, choice and a sustainable future

Choice is considered central to western capitalist approaches. You should be able to consume what you want, when you want it – and you should have a variety of prices, styles, qualities and speed of delivery.

The availability of choice has burgeoned with globalism, fuelled to a large extent by access to low wage labour in different parts of the world, advancements in technology and growing affluence for many. The current pandemic has created at least a blip, or pause for thought, as global supply chains have been disrupted.

The illusion of choice

But how real is this choice and does it really serve our needs? What about our long-term needs beyond the endorphin high of a new purchase?

In modern western economies choice has been part of the consumer dream, but how well does it serve our needs? The answer appears to be – not very well, either in the short term or the long term.

Research has shown that too much choice can be detrimental to mental health. The psychologist Barry Schwartz used the example of jam in his book to argue his ‘Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less’. In the study psychologists presented consumers with either 24 or 6 varieties of jam to taste and buy in a shop. The larger number attracted more people but similar levels of tasting. However, only 3% of people exposed to the 24 jams purchased any whereas 30% of the people offered only 6 varieties bought a jar.

He suggested that too much choice made people uncomfortable through ‘choice overload’ making it more difficult to either ‘satisfy personal needs’ or ‘maximise value’ (the two main behaviour groups he identified), ultimately leading to lower sales.

So, is capitalism undermining itself? Yes, to some extent through offering too much choice it is bewildering and alienating consumers – and if more choice also equates to greater impact it is also undermining its own long-term ability to operate. But of course, there is more to it.

In consumer terms, choice is about making us feel good – or better. It therefore adds an emotional aspect to the task of obtaining something we want, or indeed need. But Schwartz identified a third aspect, that the choices we make are also a message to the world about who we are. He argued that this was also a function of having many choices. When you have no or little choice then your selection reflects little upon you externally. However, when the potential choice is large, then your selection can be seen to say something about who you are. Of course, this behaviour is used commercially to differentiate goods and services. It is also used for performance in sustainability for example buying organic produce or fair-trade clothing, cynically also referred to as ‘virtue signalling’.

Consumer approaches to choice

If sustainability requires the purchase of better or less damaging goods and services who is going to choose them? While unsustainable products remain legal and available, there are two main options. Either for business to make the choice or for consumers to. Where should the burden lie?

The authors have worked in sustainability for many years. We’ve both heard the phrases ‘if people want it we’ll sell it’ and ‘we just need consumers to demand this’. And indeed, the proportion of ‘environmentally conscious’ consumers has steadily (and slowly) grown in recent years. But they remain a minority in practice and can be influenced by economic circumstances. For example, recessions tend to produce a ‘flight to value’ or a preference for economy goods and brands. Economy goods and services do not always perform well in sustainability terms, although this is not universally true.

Many people tend to say they want sustainable products, but in practice they don’t tend to buy them. Writing in HBR, Katherine White, David J. Hardisty, and Rishad Habib suggested the ‘Green Consumer’ was elusive they reported that:

“65% said they (consumers) want to buy purpose-driven brands that advocate sustainability, yet only about 26% actually do so.”

This ‘intention gap’ is a big one and it poses a challenge for companies and for society in meeting sustainability goals.

Barriers to ‘good choices’

In practice there are several barriers to making sustainable choices as a consumer, these include:

1. Sustainable product knowledge – how can you assess that a product is sustainable? Do you have the right information at hand, is it relevant and accurate? This is a very important and difficult area. Few people are equipped with the knowledge to make ‘better’ decisions across the value chain and navigate the multiple criteria that could be relevant to assessing product/service sustainability (for example, raw materials, renewable materials, energy footprint, renewable energy, transport impacts, manufacturing impacts, toxic substances, working conditions, child labour, conflict minerals, deforestation, animal welfare, product reliability, repairability, disposability, recyclability etc.)

2. Market knowledge – which are the best/least damaging products available on the market? For many products/segments there is little real choice in meaningful sustainability performance (for example laptop computers or mobile phones). In others there are relatively better choices in terms of some material aspects.

3. Access/availability – there may be some better choices (for example Fairphone) but these are not generally available from high street outlets or via major telecom service providers.

4. Utility – with some specific products/services the preferable option from a sustainability viewpoint may not have the same utility as market leading options. Again, Fairphone presents a good example, you’re swapping repairability, fair materials and labour sourcing and durability for cutting edge performance.

We also know that any given time, people have a limited amount of time, patience and attention. Making ethical choices requires a mental processing overhead (to deal with the barriers outlined above) and sometimes this is not possible against the background of an often-overwhelming set of decisions.

So, is it sufficient for companies to place more ‘sustainable’ options in the market and leave it to consumers to make the ‘right’ choice? After all the customer is always right? Right?

Company choices

Fundamentally businesses need to align with customer requirements. If they do not fulfil a need or want at the right time, place and cost, then their financial sustainability will be under threat.

But how large is the gap between customer requirements (encompassing wants and needs) and more sustainable choices? If substantial, it is unlikely that a company can continue to service that gap in the long-term anyway as increasing questions will be raised about its licence to operate.

The greatest conflict is often seen as cost. In general, more sustainable goods cost more than less sustainable ones. This is largely true where the true cost (including externalities) is not included in the sticker price and where a ‘sustainable’ option goes part way to addressing those externalities and in doing so the price increases.

For example, a BCI (Better Cotton Initiative) T Shirt that is Bluesign Certified is likely to cost more than one made from child labour sourced cotton, sewn in factory with poor working conditions which pays poverty wages.

How can this cycle be broken, and minimum standards adopted? It is one of the fundamental conundrums of sustainable businesses and requires systems, regulatory and economic changes. But where can businesses make a difference?

We would argue important improvements can be made by companies ratcheting up what is acceptable and normal practice.

Considerations such as environmental impact, labour conditions and impacts arising from use and disposal are all relevant.

But why would companies be best placed to make these choices and what benefits would they get?

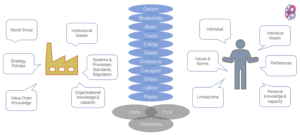

As the figure suggests, businesses have far greater capability and ability to make informed choices and stay up to date with changing circumstances.

Not only are they best placed to make trade-off decisions and source more sustainable products, but they also have a responsibility to do so. Some may argue that this is ‘choice editing’, removing the moral right for consumers to choose what they want – and to some extent of course this is true. Businesses operate within a complex envelope of constraints including legality, regulations, feasibility, economics, reputation, availability, market and commercial criteria. As a result, companies make product (and service) related choices every day, and largely they are hidden from consumers.

Businesses do edit choices continually, they make frequent decisions about what fits their strategy, what is profitable, what’s acceptable and what customers will buy. Dave Lewis, Tesco CEO, notably culled 30% of 90,000 product lines, dramatically reducing choice – or relieving anxiety depending upon your outlook!

Our argument is that ‘editing’ should also be done with a strong ‘sustainability filter’ applied, informed by the values and strategy of the company.

Who leads?

How much, and how fast this is done therefore becomes an issue of leadership.

Businesses are at a crucial leverage point in the system – they need to step up and lead. To paraphrase Henry Ford – “you can have any product you want as long as it’s sustainable.”

In some ways it could be argued that will reduce choice, and it is crucial that the drive towards sustainability is an equitable as possible. If we go further and faster down the road to sustainability, we will get better choices. Better choices as consumers – and better choices as businesses.

This future will be better for businesses because they will be operating in an area of choice, not one dogged by regulation, scarce resources or possible mass consumer outrage.

Recently Unilever decided to phase out fossil fuel-based ingredients from their cleaning products by 2030.

This is a change that could become forced upon companies soon anyway. However, now it is relatively novel and could also be a risk.

But the flipside of risk is of course opportunity, the opportunity to decouple from non-renewable raw materials, to move ahead of regulation and meet (emerging and growing) customer sentiment.

But seeing the real opportunities for a company requires flipping the equation. We have looked at product choice, but this is far more than a product opportunity. It must rise above the confusion and illusion of choice to be viewed as a real strategic opportunity.